· Michele Mazzucco · Post · 10 min read

Busting the myth — what that long queue really means

Long lines often feel like proof of success—but that’s not always the case. In this article, we explain why queues form, how perception can mislead, and what they actually reveal about your operations. Spoiler: it is not only about demand.

You might have stood in a long line at a popular coffee shop, waited endlessly for concert tickets online, or seen crowds forming outside a new store opening, and assumed that these queues are a clear sign of sky-high demand. It is a common belief: longer queues must mean that the product or service is incredibly popular and in short supply. After all, why else would people wait for hours?

But what if that assumption is wrong?

Long queues are often mistaken for signs of overwhelming demand. In reality, they can be red flags for poor system design, artificial scarcity, outdated infrastructure, or mismanaged expectations.

While the line might look like success, queues can be influenced by a variety of non-demand-related factors, such as operational inefficiencies, marketing strategies, or even psychological biases. As an informed consumer or business owner, recognizing these nuances can help you make better decisions, whether you are deciding where to spend your time or how to manage your operations.

Table of contents

- The psychology behind the queue

- The operational truth behind queues

- Artificial scarcity and engineered delays

- Why the myth persists

- What to look for instead

- Conclusion: Queue ≠ Demand

The psychology behind the queue

Queues are public, emotional, and persuasive. One glance at a snaking line supplies instant social proof: If all these people think it’s worth waiting for, maybe I should too.

The assumption that a long line signals high demand is rooted in well-studied behavioral biases. A waiting line usually triggers the idea that others must know something we don’t—if people are willing to wait, it must be good. Combine that with the scarcity heuristic—our tendency to value things more when they appear limited—and the queue becomes a powerful visual signal of supposed value.

Daniel Kahneman, Nobel laureate and author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, described this shortcut as a cognitive bias: in the absence of full information, we use what’s most salient—like a line—to make assumptions. The longer the line, the more impressive the product or service must be.

But these are assumptions—not facts.

Let’s bust this myth and explore why those seemingly endless lines often aren’t just about overwhelming demand, but are frequently a symptom of other, less glamorous, factors.

The operational truth behind queues

In operational terms, queues arise when the arrival rate exceeds the processing rate. That’s it.

While high demand can certainly contribute to long queues, it is rarely the sole or primary driver, especially in situations where queues are consistently long or unpredictable. Indeed, that mismatch can also be due to poor throughput, inefficient task handling, limited staffing, or systemic design flaws.

As we break down in our piece on Little’s Law, the length of a queue reflects not just how many people are coming in, but how quickly and effectively they are being served, and often, the processing rate is the weakest link.

Let’s look deeper at the operational realities that inflate queue lengths, independent of stratospheric demand.

1. Insufficient processing capacity

This is perhaps the most common culprit beyond simple demand. Imagine you are at a supermarket with five checkout lanes, but only two are open. The demand might be moderate – a steady stream of shoppers – but because the processing capacity (the number of open lanes) is low, a queue quickly forms at checkout.

This isn’t just about staff numbers. It can be about:

- Too few service points, e.g., only one ticket window for a busy train station, or one counter in a popular bakery.

- Limited equipment. Examples include not enough coffee machines during the morning rush, or only one printer for a high-volume print shop.

- Physical space constraints, like a small waiting area or narrow corridor that forces a line to snake externally.

Your demand might be moderate, even predictable, but if the infrastructure or staffing isn’t scaled to handle that demand efficiently, you will see queues form, giving the illusion of overwhelming demand.

2. Inefficient processes and workflow

Sometimes a system has the capacity but not the flexibility. Consider a restaurant that is fully staffed but lacks workflow coordination: a host that seats all parties at once, overloading the kitchen. The restaurant will back up, not because of high volume, but because of poor pacing. Or a clinic where every patient is treated as a walk-in with no appointment triage, leading to long wait times even when rooms and doctors are available.

Here, the culprit may be:

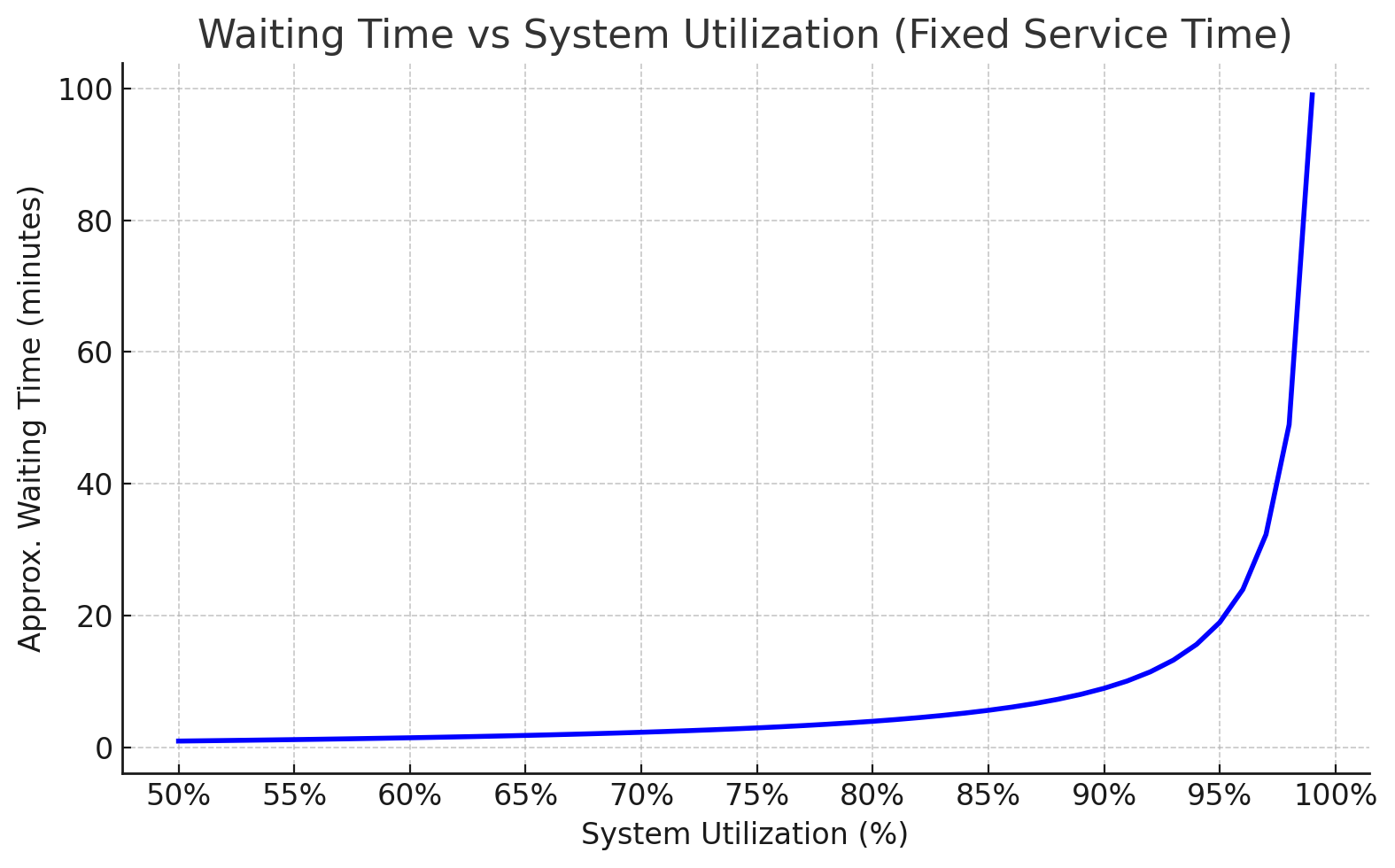

- Complex or slow procedures increase average service time—and in high-demand systems, even modest slowdowns can dramatically inflate waiting times. This effect is especially pronounced when systems run near full capacity, as shown in Figure 1.

- Poorly trained staff who are slow on the register, unfamiliar with procedures, or inefficient in their tasks directly reduce the processing rate. They aren’t necessarily lazy; they might be new, poorly trained, or working with inadequate tools.

- Lack of specialization or flow. If the same person has to take the order, make the product, package it, and take payment, any delay in one step holds up the entire process for everyone else. A streamlined flow, potentially with specialized roles, could process the same volume much faster.

3. System design flaws

Sometimes, the problem lies in the physical design.

- Poor queue management: in previous articles we have discussed how a single queue for multiple service points is often more efficient than multiple individual queues, as it eliminates the frustration of choosing the “slow” line. If a business uses an inefficient queue system (or no system at all), lines can appear longer and move slower than necessary.

- Technology issues: glitchy point-of-sale systems, slow internet connections, or unreliable equipment can bring the entire service to a halt or drastically reduce its speed. A server crash during a busy period won’t mean demand suddenly spiked; it means capacity dropped to zero.

- Unoptimized layout: a poorly designed physical space that causes customers to collide, search for items, or navigate confusing paths adds micro-delays that accumulate and slow the overall flow to the service point. We explored this dynamic in our post on queueing strategy and layout.

4. Behavioral factors (customers and staff)

Often, queues result from behavioral friction: the people in the system, or the people running it, are the source of the delay.

- Customers not prepared, forms missing, confused instructions, or delayed decisions. These small hiccups compound to make lines grow even when the volume is reasonable.

- Complex orders or requests can significantly increase their processing time, holding up everyone behind them.

- A highly efficient staff member might process transactions quickly, while a struggling colleague next to them creates a bottleneck that the faster staff member can’t fully compensate for.

Artificial scarcity and engineered delays

One reason the queue = demand myth persists is that some organizations intentionally lean into it. Scarcity is a marketing tool, and it’s often deployed with precision. From streetwear brands to ticketing platforms, queues are sometimes curated—not to handle demand efficiently, but to create buzz.

Consider sneaker culture. Nike’s SNKRS app regularly hosts limited-edition drops that seem to draw overwhelming interest. But investigations and industry analysis (like those from Business Insider) have shown that much of the traffic during these events is generated by bots and resellers, not individual sneakerheads. The queues are inflated by automation, not popularity.

Or take the infamous case of Ticketmaster during the Taylor Swift Eras Tour ticket release. Millions of fans were stranded in digital queues, and many assumed they were part of an unprecedented demand wave. But as we detail in our article on digital queue abandonment, the reality was a failure of planning, capacity modeling, and bot filtering. The platform wasn’t overwhelmed by Swifties—it was overwhelmed by poor queue management.

Restaurants and cafés sometimes exploit a similar visual. In urban centers, it’s common for trendy spots to avoid reservations and waitlists. The result is a long visible queue, feeding a feedback loop: people see a line and assume the food is worth the wait. Yet OpenTable data shows over 40% of wait time issues are due to table-turn delays, inefficient floor management, or labor shortages. Again, the line is the symptom—not the product of extraordinary demand.

Even major retail events like Black Friday demonstrate the illusion. Doorbuster deals encourage early arrival and scarcity-chasing. But studies show that per-capita spending during Black Friday events has declined in recent years, even as lines still wrap around buildings. Moreover, analyses from retail experts at firms like McKinsey & Company reveal that a large portion of these queues can be attributed to marketing strategies, not demand: many people join the queue out of curiosity or the fear of missing out (FOMO), only to leave without purchasing anything once they realize the deals aren’t as attractive as advertised.

And then there is the public sector. Government services, like DMVs or immigration offices, often appear overwhelmed. But World Bank research into single-window service centers found that queues often form because of capped daily intake, not because everyone in line arrived at once. A system that handles 50 customers per day—regardless of how many show up—will always have a queue.

Don’t be fooled: a table of contrasts

To reinforce the disconnect between perception and reality, here is how several real-world scenarios stack up.

| Scenario | Queue size | Real demand level | Primary reasons for long queue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 📱 New smartphone launch (e.g., Apple iPhone) | Very long (hours or days) | High | Marketing hype, social proof, and reseller activity |

| 🍣 Popular restaurant during peak hours | Moderate to long (30-60 minutes) | Moderate | Understaffing or limited seating capacity |

| 🎸 Online ticket sale for a concert | Digital jam | Variable | System limitations, bot interference, or phased releases |

| 🏢 DMV office renewal process | Long (1-2 hours) | Low | Bureaucratic delays and single-service points |

| 🛒 Routine grocery checkout | 5 minutes | High | Efficient operations and multiple lanes |

Why the myth persists

So why does this myth endure? Because associating queues with demand is the simplest explanation. And it is intuitively appealing too. We see a line, we think “popular.” It requires less critical thinking than analyzing potential system failures or capacity constraints.

For businesses and operators, the myth can even be convenient – a long queue looks like success, like everyone wants what they have. It can be a perverse form of social proof, even if it is a sign of frustrating inefficiency to those stuck in line.

But mistaking queue length for performance can be costly. It hides underlying problems: poor flow, inconsistent staffing, technical bottlenecks. Worse, it can lead to misguided fixes. For example, hiring more staff to handle long lines might seem logical, but as we have shown in The Myth of More Staff, simply adding people doesn’t always improve speed. Optimization is often about rethinking, not reinforcing.

What to look for instead

If you are a customer, learn to observe beyond the surface. Ask: is the queue moving? Are some staff idle while others are overwhelmed? Is the process predictable or chaotic? These details tell you more about the experience than the number of people in line.

If you are managing the queue, instead, start with diagnostics. Where is the true bottleneck? What can be parallelized? What is dragging the average service time? Remember, customers stuck in line are often unhappy customers. They are also potential lost customers who see the line and walk away. Fortunately, in many cases, small interventions—self-check-in, better signage, batch processing—deliver better results than large staffing or system overhauls.

💡 At QueueworX, we have written extensively about the real levers that move queues, including load balancing, layout design, arrival smoothing, and demand forecasting. Whether the issue is digital congestion or on-site foot traffic, the principle is the same: systems, not just volume, determine the wait.

Conclusion: Queue ≠ Demand

A long queue might indicate high demand—or it might be a red flag. Without understanding the underlying system, it’s impossible to know which.

💡 Next time you see a long line, resist the reflex to equate it with runaway demand. You might just be witnessing a masterclass in the hidden art—and cost—of inefficiency.

By shifting the conversation from what the queue looks like to what it really represents, we not only improve the customer experience—we also build smarter, more resilient systems.

If you want to dig deeper, check out our posts on queue design, digital congestion, and service efficiency. We believe a better system starts not with assumptions—but with insight.

📬 Get weekly queue insights

Not ready to talk? Stay in the loop with our weekly newsletter — The Queue Report, covering intelligent queue management, digital flow, and operational optimization.