· Michele Mazzucco · 15 min read

Virtual queues from scratch, Part 2: implementing the Lobby Service with Redis

In Part 1, we established the architectural blueprint for our virtual queue. Now, it's time to translate that design into working code. This article kicks off the implementation by bootstrapping our Lobby Service in Python and integrating Redis to manage the queue's state. You will learn how to handle the first user requests and build the foundation for the entire waiting room.

In the first article of this series, we explored the core concepts of virtual queues and made a critical architectural decision: to build our system around a Pull model. This approach, as we discussed, offers greater resilience and efficiency, especially in modern cloud environments.

With our architecture defined, it’s time to write the first lines of code. The heart of our waiting room is the Lobby Service, the entry point for all users. In this post, we’ll bootstrap this service using Python and introduce its most important companion: Redis, which will act as our high-performance, in-memory state manager for the queue.

By the end of this article, you will have:

- A running ASGI application for our lobby service.

- A Redis client connected and ready to manage data.

- The core logic to add a user to the queue and retrieve their status.

- A solid, testable foundation for the more advanced features we will build in Part 3.

As mentioned in our tech stack breakdown, we are starting with a minimal ASGI server to keep latency low and using Redis for its speed—two key ingredients for a performant queue.

Let’s dive in and get our lobby up and running.

Table of contents

- Part B – The “How”: core queue logic

Part B – The “How”: core queue logic

1. Building the Lobby Service

We expose only three hot‑path endpoints, so we can drop the heavy router, middlewares, and exception hierarchy that frameworks like FastAPI carry. A 50‑line map‑based router plus msgspec structs is enough:

POST /join: issue token, returnJoinQueueResponseGET /position/{token}: returnPositionResponseGET /qsize: returnQsizeResponse

import re

from typing import Awaitable, Callable

from typing import Optional

from msgspec.json import Encoder

Handler = Callable[..., Awaitable[None]]

class Router:

def __init__(self):

# For just 3 endpoints, a list is faster than a dict

self.routes = []

self.encoder = Encoder()

# pre-encode errors

self._not_found_body = self.encoder.encode({"detail": "Not found"})

self._not_found_headers = [(b"content-type", b"application/json"), (b"content-length", str(len(self._not_found_body)).encode()),]

# ...

def route(self, method: str, path_pattern: str):

""" Register a regex route handler"""

def decorator(fn: Handler):

self.routes.append((method.upper(), re.compile(f"^{path_pattern}$"), fn))

return fn

return decorator

async def dispatch(self, scope, receive, send):

"""

Dispatch the request to the target handler, if found, else return HTTP 404.

HTTP 404 and 500 error messages are pre-encoded.

"""

method = scope["method"]

path = scope["path"]

for route_method, pattern, handler in self.routes:

if method == route_method:

match = pattern.match(path)

if match:

# Error handling omitted for brevity

return await handler(scope, receive, send, **match.groupdict())

return await self._not_found(send)

async def _not_found(self, send):

await send(

{ "type": "http.response.start", "status": 404, "headers": self._not_found_headers }

)

await send(

{"type": "http.response.body", "body": self._not_found_body}

)

async def respond(

self, send, status_code, data, extra_headers: Optional[list] = None

):

body = self.encoder.encode(data)

headers = [

(b"content-type", b"application/json"),

(b"content-length", str(len(body)).encode()),

]

# Add any extra headers passed in

if extra_headers:

headers.extend(extra_headers)

# HTTP headers and body must be sent separately

# https://asgi.readthedocs.io/en/latest/specs/www.html

await send(

{ "type": "http.response.start", "status": status_code, "headers": headers }

)

await send(

{ "type": "http.response.body", "body": body }

)Hence, we can bootstrap our virtual lobby with the following straightforward design:

- Join queue (

/join): Users are assigned a unique ticket (token) and placed at the back of the queue. - Queue position (

/position/<token>): users periodically check their position in the queue, along with an estimate of their waiting time. This also extends the token time-to-live (TTL). - Admission control: requests can be rejected if the estimated waiting time becomes too large, protecting the backend from overload.

- Ticket expiry: users may get distracted, change their mind, or face technical issues. Tokens expire after a certain time if users abandon the queue, ensuring accurate queue management.

Note that as part of the ASGI specification, HTTP headers and body must be sent separately (see code snippet above). Also, we have to implement the lifespan protocol:

from msgspec import Struct

from router import Router

class JoinQueueResponse(Struct):

id: str

position: int

wait: float

class PositionResponse(Struct):

position: int

wait: float

variance: float

class QsizeResponse(Struct):

len: int

class AsgiLobby:

def __init__(self):

self.router: Router = Router()

# ...

# Register routes

self.router.route("POST", "/join")(self.handle_join_queue)

self.router.route("GET", r"/position/(?P<token>[a-zA-Z0-9\-]+)")(self.handle_position)

self.router.route("GET", "/qsize")(self.handle_qsize)

async def __call__(self, scope, receive, send):

if scope["type"] == "lifespan":

await self.handle_lifespan(scope, receive, send)

elif scope["type"] == "http":

await self.router.dispatch(scope, receive, send)

async def handle_lifespan(self, scope, receive, send):

"""

Lifespan protocol https://asgi.readthedocs.io/en/latest/specs/lifespan.html

"""

while True:

message = await receive()

if message["type"] == "lifespan.startup":

# 1. Compile math code via Numba by triggering the relevant functions

# 2. Setup Redis connection pools and metrics server

# 3. Load Lua scripts

# 4. Initialize lobby state

# 5. Create background tasks

await send({"type": "lifespan.startup.complete"})

elif message["type"] == "lifespan.shutdown":

# 1. Stop all tasks

# 2. Close Redis connection pools

await send({"type": "lifespan.shutdown.complete"})

break

# ... handle_join_queue(), handle_position() and handle_qsize() functions2. Leveraging Redis for managing queue state

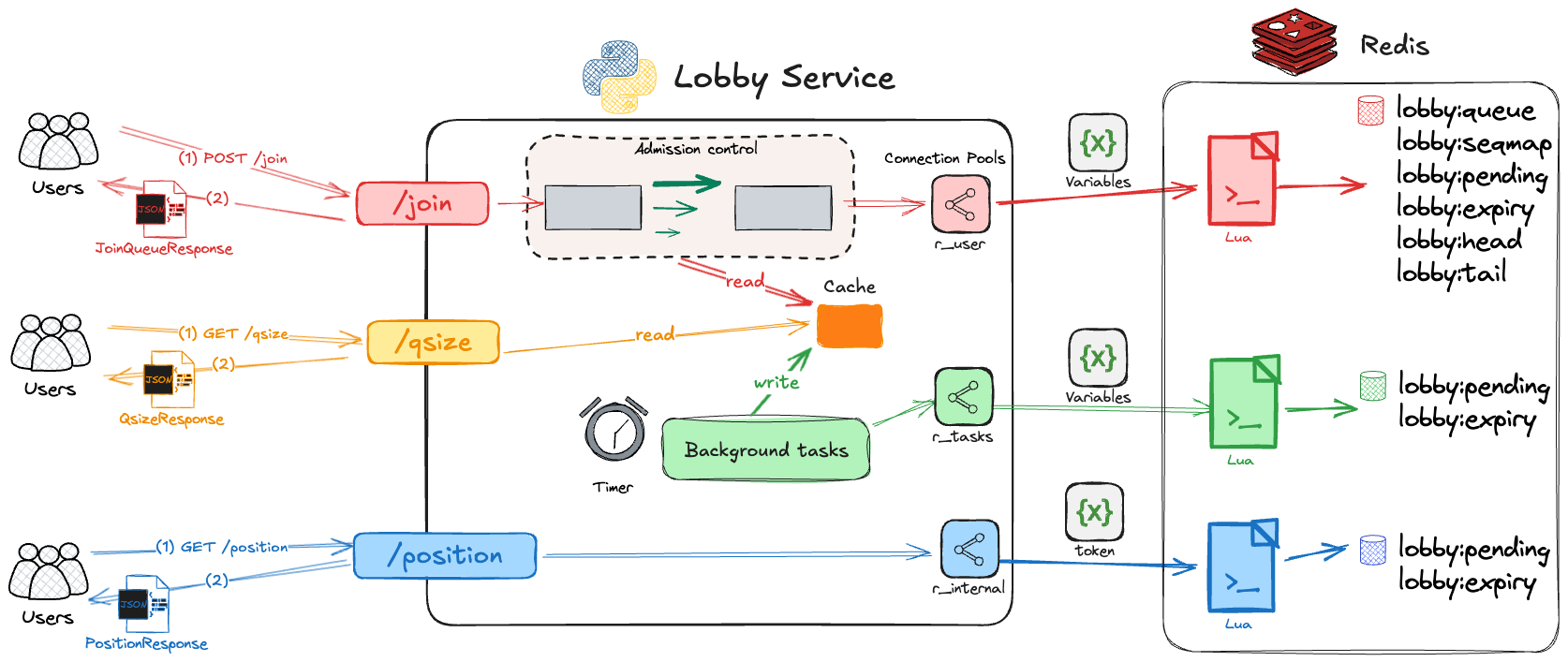

Redis excels at fast, atomic operations—perfect for managing our queue state reliably. Here is how we will use Redis in our virtual waiting room:

- List (

lobby:queue): Tracks users waiting in line. Workers use blocking pop operations to efficiently handle requests. - Hash (

lobby:seqmap): Maps tokens to their sequence numbers, enabling quick position lookups. - Sorted Sets:

- Pending (

lobby:pending): Maintains an ordered list of active tickets, allowing precise position checks even when some users leave or timeout. - Expiry (

lobby:expiry): Manages ticket expiration timestamps, automatically handling abandoned tickets without expensive full-queue scans.

- Pending (

- Counters (

lobby:head,lobby:tail): Keep track of queue progress efficiently and consistently.

While these data structures form the core of our state management, a robust, high-performance implementation requires several key optimizations. To reduce latency on frequent reads, we’ll introduce a local cache. To ensure data consistency during writes, we’ll rely on atomic Lua scripts. And to prevent bottlenecks, we’ll isolate traffic with dedicated connection pools.

The diagram below puts all these pieces together, illustrating the complete flow of a user request through our optimized lobby service. You will find a detailed breakdown of how we implement each of these optimizations in the section that follows.

💡 Does the Redis variant matter?

For our demo we use Redis 8, but large-scale systems often consider alternatives. Here is what matters for a virtual lobby:

| Feature | Redis 8 | KeyDB | Dragonfly | Valkey |

|---|---|---|---|---|

BLPOP, RPUSH, ZADD, etc. | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Lua scripting / atomic pipelines | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

TDIGEST.* (RedisBloom) | ✅ builtin | ⚠️ (RedisBloom module) | ❌ not yet | ❌ not yet |

| Multi-threaded ops | ✅ I/O threading | ✅ (all commands) | ✅ (core architecture) | ✅ I/O threading |

| Performance at 10k+ ops/sec | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Pub/Sub / WebSocket support | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Actively maintained | ✅ (Redis Inc.) | ⚠️ slower/stalled | ✅ very active | ✅ (Linux Foundation) |

| License | AGPL v3 | BSD-3 | BSL 1.1 | BSD-3 |

To summarize:

Redis 8.0+: Ideal choice with built-in t-digest support, simplifying percentile computations (we use them for statistic purposes) without additional modules.

KeyDB: Offers high performance but lacks native

t-digestsupport; integrating RedisBloom may be complex.Dragonfly: compelling new engine — if

t-digestsupport lands, it could be ideal for virtual queues that need ultra-low tail latency.Valkey: Potentially viable with module support; ensure necessary modules are available and stable.

3. Implementation notes: optimizing for performance and reliability

Beyond the fundamental data structures, several implementation details are crucial for a robust and performant queue. We can group these into four key areas: ensuring data consistency, accurately estimating wait times, monitoring the system, and managing resources effectively.

3.1. Atomicity and performance in Redis

To maintain data integrity under load, operations must be atomic.

Ensuring atomicity with Lua scripts: Redis pipelines are excellent for performance as they group commands to reduce network round-trips—however they don’t ensure atomicity. For operations that must be atomic, like updating shared counters, we use Lua scripts. Redis guarantees a Lua script will execute without interruption, which is akin to a stored procedure in a relational database, where the entire logical unit of work is processed atomically on the server. This guarantees consistency while keeping our Redis load low.

Caching Lua scripts: To avoid the small overhead of loading a script on every execution, we use the

LOADcommand at startup to cache required scripts. We then trigger the cached versions usingEVALSHAcommands, which is much more efficient in high-traffic scenarios.Local caching for frequently accessed data: To minimize Redis queries under heavy load, we implement a local cache for frequently accessed, relatively stable data such as arrival rates, service rates, or queue size. These values are refreshed periodically (e.g., once per second) by a background task. This approach strikes a balance between data freshness and system performance:

- It significantly reduces the number of Redis queries, lowering network overhead and Redis server load.

- It provides near-instant access to these statistics for rapid decision-making in the application layer.

- The slight delay in data freshness (up to 1 second) is typically negligible for these metrics, especially under high load conditions where large-scale changes are unlikely to occur within sub-second intervals.

- This trade-off between absolute real-time accuracy and system performance is justified, as the benefits of reduced load on Redis and faster local access outweigh the minimal staleness of data in most scenarios.

By implementing this local caching strategy, we ensure that our system can handle high traffic volumes efficiently while maintaining a good approximation of the current state, only incurring a small, acceptable delay in reflecting the most recent changes in the monitored metrics.

Balancing write pressure: For metrics that are self-contained, like service times, we can record them and periodically flush them to Redis in batches using a background task. However, data like inter-arrival times requires reading and updating a shared timestamp atomically, making a per-event Lua script the correct choice to preserve correctness:

-- Lua script updating the interarrival interval statistics -- Current time local now = tonumber(ARGV[1]) local last = redis.call("GET", "arr:last_ts") if not last or now > tonumber(last) then if last then local delta = now - tonumber(last) -- Statistics used to compute ca2 redis.call("INCRBYFLOAT", "arr:sum", delta) redis.call("INCRBYFLOAT", "arr:sum2", delta * delta) redis.call("INCR", "arr:count") end -- Update timestamp of the last arrival redis.call("SET", "arr:last_ts", now) end

3.2. Accurate wait time estimation

- Using the right math: The

t-digestdata structure is excellent for calculating percentiles, but it does not give you the mean. To estimate the average service time, we compute a simple running total in Redis (average = sum / count) - Accounting for traffic variation: Real-world traffic is rarely perfectly uniform. To account for this, we compute the squared coefficient of variation for both service times (cs²) and inter-arrival gaps (ca²) using Redis counters, which lets us approximate wait times more accurately without storing historical samples:

async def cv2(self, min_samples: int = 1000) -> float: s, s2, c = await self.r.mget(self.sum_key, self.sum2_key, self.count_key) c = int(c or 0) if c < min_samples: return 1.0 # assume exponential mean = float(s) / c mean_sq = float(s2) / c mean2 = mean**2 variance = mean_sq - mean2 return max(variance / mean2, 0.01) - Avoiding early noise: To prevent volatile estimates when the service first starts, we assume standard Markovian traffic (cs²=1, ca²=1) until we have collected at least 1,000 samples.

3.3. Monitoring and observability

You can’t manage what you can’t see.

Collecting metrics: We run a background task every second that collects key metrics (like the current queue length) and sends them to a time-series database like VictoriaMetrics or Prometheus. This task uses the

prometheus_clientlibrary to format the data:from redis.asyncio import Redis from prometheus_client import CollectorRegistry, Gauge metrics_reg = CollectorRegistry() # private registry queue_len_g = Gauge("lobby_queue_length", "Tokens waiting in Redis list", registry=metrics_reg) start_http_server(9100, registry=metrics_reg) # expose the private registry async def queue_sampler(ctx: AppContext, stop_event: asyncio.Event) -> None: lobby: LobbyState = ctx.lobby r: Redis = lobby.redis # internal Redis pool while not stop_event.is_set(): queue_len = await r.zcard(ctx.lobby.keys.pending) queue_len_g.set(queue_len) # ... other metrics await asyncio.sleep(1)Handling hot-reloading: When using Uvicorn’s reloader, you must create a private

CollectorRegistry(see code snippet above). If you don’t, each reload will attempt to re-register the same metric, causing a “Duplicated timeseries” error in Prometheus.

3.4. Resource management and stability

A mismanaged resource can bring the whole system down.

Isolating Redis connections: A key bottleneck can emerge from Redis connections. A worker performing a blocking list pop (

BLPOP) holds a Redis socket open. With just 10 workers, a single connection pool of 10 would be exhausted, bringing the whole system to a halt. To prevent this system-wide stall, we must isolate the connection pools based on their function.from typing import NamedTuple from redis.retry import Retry from redis.backoff import ExponentialBackoff from redis.asyncio import BlockingConnectionPool, Redis class RedisPools(NamedTuple): r_user: Redis # Redis pool for /join r_internal: Redis # Redis pool for /position r_tasks: Redis # Redis pool for background tasks def create_redis_pools(debug=False) -> RedisPools: # retry 3 times, maximum delay 2 seconds retry = Retry(ExponentialBackoff(cap=2, base=0.1), 3) pool_user = BlockingConnectionPool.from_url( REDIS_URL, max_connections=2 * MAX_WORKERS + 10, timeout=1, decode_responses=True, ) r_user: Redis = Redis(connection_pool=pool_user, health_check_interval=5, retry=retry) # r_internal ... # r_tasks ... return RedisPools(r_user=r_user, r_internal=r_internal, r_tasks=r_tasks)The above setup creates three distinct Redis connection pools:

- The

r_userpool is generously sized to handle incoming user traffic without delay. - Meanwhile, the

r_internalpool is used by our workers, isolating their blocking operations so they can’t affect new users joining the queue. This pool is also used to serve requests hitting the/positionendpoint, which is an internal-facing endpoint for users already in the system. - Finally,

r_taskshandles low-priority background jobs. This separation ensures that a bottleneck in one part of the system doesn’t compromise the others.

Also, note that each Redis pool is configured with automatic retry in case of errors and performs automatic health checks every 5 seconds. In production, we would also implement the Circuit Breaker pattern, e.g., as described here.

- The

Managing the garbage collector: Python’s garbage collector can compete with the

asyncioloop for the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). To ensure smooth performance, we disable automatic garbage collection and instead run it periodically on a schedule via a background task:async def gc_task(stop_event: asyncio.Event, interval: float) -> None: gc.disable() try: while not stop_event.is_set(): await asyncio.sleep(interval) gc.collect() finally: gc.enable()

4. The API in action: example requests

Here is what the output of our three endpoints looks like.

4.1. A user joins the queue

A POST request to /join places the user in the queue and returns a unique token, the initial position, and the estimated waiting time in the response body.

$ curl -i -X POST http://localhost:8000/join

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

x-poll-after-seconds: 15.57

...

{"id":"bdea74e6-5c19-40c0-9fc3-fef8cc0a7485","position":366,"wait":33.68}One custom HTTP header, x-poll-after-seconds, is included. This header indicates the maximum amount of time (in seconds) that can elapse before the next poll request is required. Polling before this deadline is fine, but polling after it could result in the token expiring and the user losing their place in the queue.

📌 Note

4.2. A user checks their position

The client polls the /position/{token} endpoint to receive updates. Each response contains the user’s current place in the queue, an updated estimate of the remaining waiting, and the uncertainty around that estimate. The x-poll-after-seconds retains its role, informing the client when the next poll should be sent.

For example, after joining at position 366, the user moves forward in the queue and receives updated wait estimates each time. This polling action also acts as a heartbeat, extending the token’s lifetime and maintaining the user’s place in the queue.

$ curl -i http://localhost:8000/position/bdea74e6-5c19-40c0-9fc3-fef8cc0a7485

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

x-poll-after-seconds: 14.33

...

{"position":318,"wait":28.82,"variance":4.45}

$ curl -i http://localhost:8000/position/bdea74e6-5c19-40c0-9fc3-fef8cc0a7485

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

x-poll-after-seconds: 10.89

...

{"position":206,"wait":18.81,"variance":3.7}

$ curl -i http://localhost:8000/position/bdea74e6-5c19-40c0-9fc3-fef8cc0a7485

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

x-poll-after-seconds: 2.19

...

{"position":62,"wait":5.33,"variance":1.96}

$ curl -i http://localhost:8000/position/bdea74e6-5c19-40c0-9fc3-fef8cc0a7485

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

x-poll-after-seconds: 1.91

...

{"position":38,"wait":3.05,"variance":1.46}As seen above, each subsequent call to /position/{token} shows the user’s progress through the queue:

- Position steadily counts down toward the front.

- Estimated waiting time (

wait) decreases as their turn approaches. x-poll-after-secondsalso drops significantly, reflecting the need for more frequent liveness checks as the user nears the front.

💡 Notes

4.3. Checking the total queue size

/qsize exposes a monitoring endpoint allowing us to quickly check the total number of users in the queue.

$ curl -i http://localhost:8000/qsize

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{"len":320}Conclusion: a running Lobby and a look ahead

We have successfully moved from the architectural blueprint of Part 1 to a tangible, running service. We built a lean, high-performance ASGI application from scratch, carefully avoiding framework overhead. We then designed a robust state-management layer using Redis, leveraging its powerful data structures like Lists, Hashes, and Sorted Sets to manage the queue, track users, and handle token expiry.

Finally, we explored critical implementation details for ensuring atomicity with Lua scripts, calculating accurate wait times, and managing resources like connection pools to build a stable and reliable system. You now have a solid, testable foundation for a virtual lobby. The complete source code for this series will be made available in a public GitHub repository in the coming weeks.

Coming up in Part 3…

Our lobby is running, but nobody is being let in yet! To test our virtual queue in isolation, we will simulate the backend services rather than building real ones. This approach allows us to create a range of traffic conditions (like bursty arrivals or heavy-tailed service times) to really put our system to the test.

In the next article, we will implement these simulated backend workers. Each worker will be a Python coroutine that:

- Removes a user from the front of the queue using the Redis

BLPOPcommand (blocking if the queue is empty). - Simulates doing work by sleeping for a configurable, random amount of time.

We will program this logic, tackle dynamic admission control, and dive deeper into handling abandoned tickets and other real-world edge cases. Stay tuned!

📬 Get weekly queue insights

Not ready to talk? Stay in the loop with our weekly newsletter — The Queue Report, covering intelligent queue management, digital flow, and operational optimization.